Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5

1.12

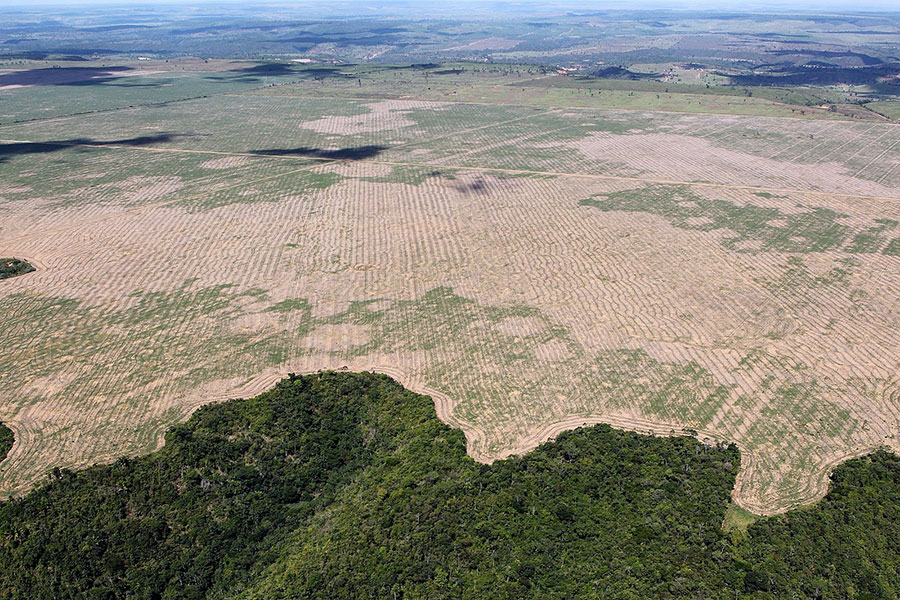

Ibama and the Federal Police are fighting a criminal group responsible for illegally extracting and trading wood from the Gurupi Biological Reserve and the Caru and Alto Turiaçu Indigenous Lands, in Maranhão, Brazil 2016, by Ibama from Brasil, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Can history be the story of different stories?

In Anneli Ekblom’s video we learn that in trying to find solutions in regards to climate change we should avoid looking at history as a linear process. She talks about how grand historical narratives might make current development seem like an inevitable outcome. In the two following activities we will take a look at a grand narrative that is becoming more and more influential – the idea that humans are now the primary driver of change in the earth system – and ask ourselves if a narrative like that can be made including many different stories.

The Anthropocene

Are the impacts by human life on the earth systems on such a scale that humanity itself (“anthro”) should be named as the prime characteristic of present times? The term anthropocene was introduced by Eugen F. Stormer and Paul Crutzen about 16 years ago as a way of describing humanities increased impact on the planet [1]. The term has since been widespread, receiving more than 28 000 hits on google scholar, and it is currently discussed if it should be adopted as the official geological term of the current era.[2] The primary argument behind this is that human activities will leave visible traces in the sediments of the earth. The impacts of nuclear weapons, fossil fuels, new materials, fertilisers, global warming and mass extinctions will remain imprinted in layers of rock. [3]

But when did the anthropocene start? A popular suggestion is at the start of a process called the great acceleration.

The Great Acceleration

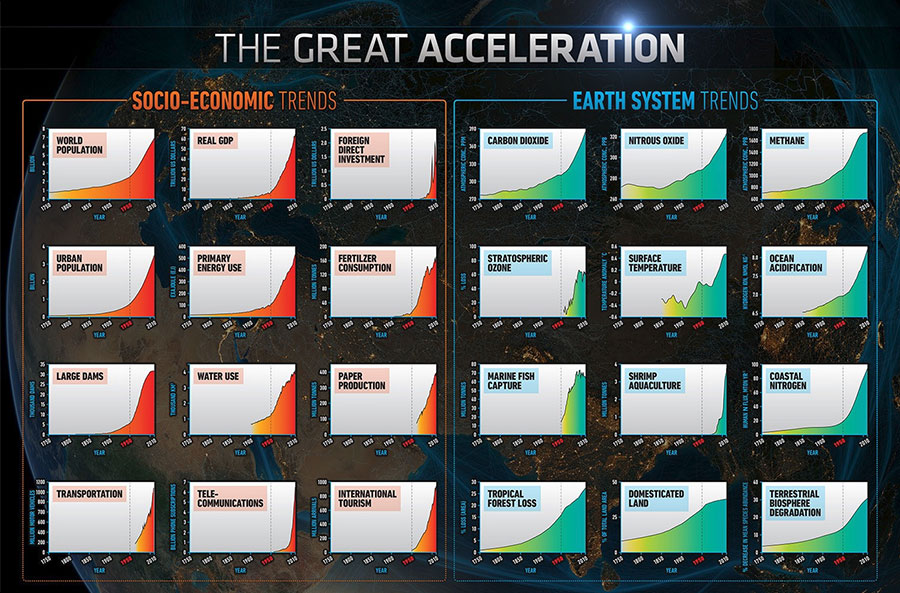

Planetary dashboard: for a higher resolution version of this picture visit anthropocene.info © IGBP.

If you look carefully at the graphs above you can see that human induced CO2 emissions rose steadily from the 1850s. This increase was made possible as societies transitioned from endosomatic (from within bodies, eg. humans and livestock) to exosomatic energy (from things outside of bodies, eg. water, wind and fossil fuels). By extracting fossil fuels on a large scale, many humans were able to consume energy differently: they could more easily transport and store energy, whilst unlocking solar energy that had been accumulated in organic matter for thousand of years. One way to understand this energy compression is through Jeffrey S. Dukes [4] estimation (interpreted by Timothy Mitchell) that:

a single litre of petrol used today needed about twenty-five metric tons of ancient marine life as precursor material, and organic matter the equivalent of the earth’s entire production of plant and animal life for 400 years was required to produce the fossil fuels we burn in a single year [5]

But even when accounting for the steady rise after of energy use during the 19th century, something extraordinary happened in the 1950s. While both world wars, despite the mobilisation in terms of armies, naval and airborne, were carried out without major increase in use of oil, the 1950s marks the start of a rapid increase that scientists later have come to call the great acceleration. As you can see in the graph this acceleration did not only concern fossil fuels – every indicator shows a dramatic rise: Human population increased from 3 to 6 billion in 50 years, the combined economic activity increased 15 fold during the same period, loss of tropical rain forests increased roughly 300% between 1950 and 2000, and the world entered its sixth great extinction. [6]

Look at this talk by Will Steffen to learn more about the anthropocene and the great acceleration.

The Great Divergence

When looking at the graphs above there is one important thing that doesn’t show – the indicators only represents the lives of a minority of mankind. The great acceleration from the 19th century also marked the escalation of another trend – the great divergence.

The creation of industrial clusters shaped the world into relations between centers and peripheries, where the peripheries produced raw materials and the centers produced refined products. This neocolonial process is sometimes called unequal trade – the unequal trade being understood as “(1) the appropriation of ‘negative entropy’ (accessible, high- quality energy and materials) from elsewhere and (2) the displacement of entropy (energetic and material disorder) elsewhere.”[7] For example, when looking at the emission of CO2:

as of 2008, the advanced capitalist countries or the ‘North’ composed 18.8% of the world population, but were responsible for 72.7 of the CO2 emitted since 1850, subnational inequalities uncounted. In the early 21st century, the poorest 45% of the human population accounted for 7% of emissions, while the richest 7% produced 50%; a single average US citizen – national class divisions again disregarded – emitted as much as upwards of 500 citizens of Ethiopia, Chad, Afghanistan, Mali, Cambodia or Burundi (Roberts and Parks, 2007).[9]

The fact that the impacts of climate change is most visible among of the lives of people in the south, while the cause is mostly due to the life of people in the north, has led the environmental humanist Robert Nixon to refer to the great acceleration and the great divergence as “the great environmental crisis and the great inequality crisis” [10].

Colonial histories and neocolonial presents

The great divergence has its roots in colonial history: many unsustainable industries descend from colonial economies.

Such examples are the current dominant methods of agriculture, forestry and other land use, which accounted for 22% of global emissions in 2019 [11] and are (in general) catastrophic for biodiversity. Anna Tsing and Donna Harraway popularised the term “plantationocene” to describe the era emerging with slave plantations and lasting to today’s monocultural agriculture, labour and incarceration practices. Tsing says:

the term plantation for me evokes the heritage of a particular set of histories involving what happened after the European invasion of the New World, particularly involving the capture of Africans as enslaved labor and the simplification of crops so as to allow enslaved laborers to be the agricultural workers. In many small, independent farming situations, dozens of crops are raised that need to be tended by farmers who are invested in attending to each one. In designing systems for coerced labor, ecological simplifications entered agriculture. [12]

Haraway says:

The plantation system requires either genocide or removal or some mode of captivity and replacement of a local labor force by coerced labor from outside, either through various forms of indenture, unequal contract, or out-and-out slavery. The plantation really depends on very intense forms of labor slavery, including also machine labor slavery, a building of machines for exploitation and extraction of earthlings. I think it is also important to include the forced labor of nonhumans—plants, animals, and microbes—in our thinking. [12]

When looking at the grand narratives of history it’s important to remember that they contain many different stories, all of which are equally important if we want to be able to learn. In the following discussion, we will look at the concept of slow violence and think more about history as a means of climate change communication.

References

- Steffen, W. et. al. (2011) The Anthropocene: conceptual and historical perspectives The Royal society, Vol. 369, Issue 1938.

- The Guardian. (2016). The Anthropocene epoch: scientists declare dawn of human-influenced age, August 29, 2016.

- Waters, C, N. et. al (2006) The Anthropocene is functionally and stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene, Sciencemag, Vol 351 Issue 6269.

- Dukes, J.S. 2003. Burning buried sunshine: human consumption of ancient solar energy. Climatic Change, 61(1-2): 31-44.

- Mitchell, T. 2009, “Carbon democracy”, Economy and society, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 399-432.

- Steffen, W. et. al (2015) The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration. The Anthropocene Review, Vol 2 (1), 81-98.

- Fischer-Kowalski, M., (1998). Society’s metabolism: the intellectual history of material flow analysis. Journal of Industrial Ecology. 2 (1), 61–78).

- Clark, R.P., (1997). The Global Imperative: An Interpretive History of the Spread of Humankind. Westview Press.

- Timmons, J. R and Parks, C. B. (2007). A Climate of Injustice: Global Inequality, North-South Politics, and Climate Policy.

- Nixon, R. (2014) The Great Acceleration and the Great Divergence: Vulnerability in the Anthropocene Presidential forum. 19 March 2014.

- IPCC. (2022). Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. [Report] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/

- Mitman, G. (2019). Reflections on the Plantationocene: A Conversation with Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing. Edge Effects. Available at: https://test.edgeeffects.net/haraway-tsing-plantationocene/

See also

- McKittrick, K. (2011). On plantations, prisons, and a black sense of place. Social & Cultural Geography 12 (8) pp. 947-63.

© CEMUS and Uppsala University