Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5

4.12

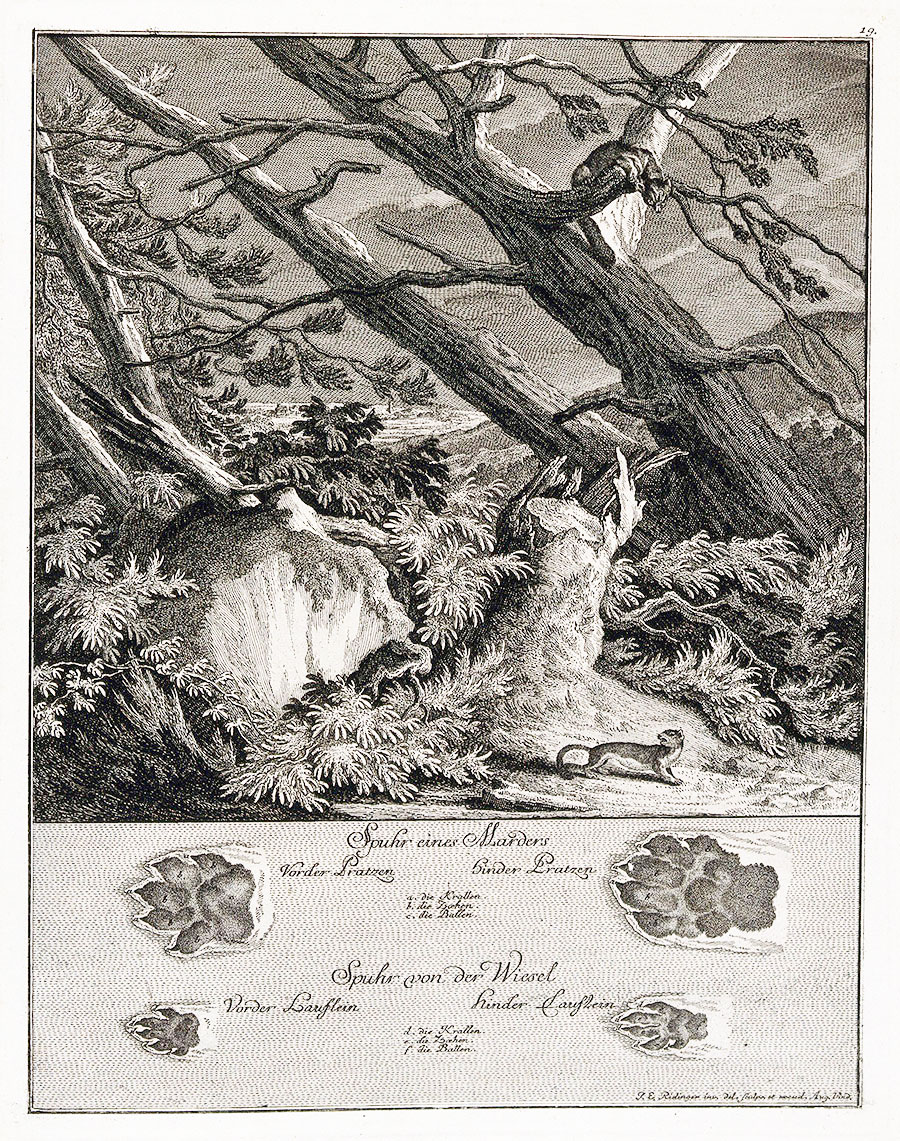

Above, a marten and a weasel on a nocturnal excursion in the forest, below, their tracks. Etching by J. E. Ridinger (1698-1767), public domain.

Investigating a place: microhistory in the field

If you’re looking to take action in a place, it’s important to know why it is the way it is. This is where history has an important role. The study of microhistory, the history of a small area or group, reveals how your particular place of interest might differ from broader trends and subvert your expectations. As a leader, it is vital to understand your context, within your scope of influence. This can mean researching the last few months of a place, or the last century.

For an example of microhistory, you can read Hayden Lorimer’s (2006) Herding memories of humans and animals.

As you visit your field site, look for:

Newspapers and newspaper archives

- A basic google search may reveal recent history, political debates, records of government decisions and notes from community meetings. Note the source of the information so you can consider how reliable it is.

- Local museums often store old newspapers or other records. Religious organisations may retain birth records.

Local memory

- This is perhaps the fastest and most helpful source of information

- What do the people you are working with know about the local area and its history? Can you pool this knowledge? Ask people about the other clues you find. Who disagrees and about what?

- How long have people lived here? Who lived here before? Why do they no longer live here?

- What was the weather like in the past? The nature? The agriculture? How has it changed?

- Ask people you meet – over coffee, in the street, in the forest, at the shops. Think of questions in advance and keep them open – ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions invite free responses.

- What do people think are important issues that should change? What are groups already working on?

Physical signs in the landscape

- Land use

-

- Is it an urban space, a forest, a grassland, a beach, a field?

- Why? How did it come to be this way and why has it or hasn’t it changed over time?

- For example, trees might have survived for hundreds of years because they are protected inside a burial area or hospital grounds, or there may have been a long-running campaign to protect a marshland.

- Is the ground wet or dry? Are there dying plants or animals? What is the weather like? What is the soil made up of?

-

- Human signs, notices, infrastructure

-

- Are there demolition or construction notices? Are there busy roads and high levels of pollution? Are there fences? Who or what are they meant to keep out or in? Is there a local group putting up posters? Is there graffiti about a particular political issue? Are there sacred places?

- Are there mysterious objects which you don’t recognise because they were built before your time? Are there ruins, buildings no longer in use, defunct groundworks, walls or ditches?

-

- Animal tracks, nests, excrement, sightings, remains, fossils

-

- Where do the tracks lead you if you follow them? Where do animals like to be in the landscape? Why do you think they choose those places?

- Did these animals evolve here? Have they been introduced later? How and why?

- Are there species which used to live here but now don’t?

-

- Plants of all sizes

-

-

- For example, lichen can indicate air pollution, and pine, rhododendron and wood sorrel grow in acidic soil.

- Are these plants ‘native’? Are they cultivated, wild or somewhere in between? Who or what put them there?

- How do they grow? For example, a woodland may grow in a wedge shape in response to the prevailing wind. What is dying and what is thriving?

- Are there species which used to live here but now don’t?

-

What each of these clues tells you will be specific to your place and time. What may seem irrelevant may, on a closer look, be directly connected to the issue you are investigating.

© CEMUS and Uppsala University