Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5

5.3

Feb. 17, 2010, U.S. President Barack Obama, accompanied by members of Congress and middle school children, waves as he talks on the phone from the Roosevelt Room of the White House to astronauts on the International Space Station.

Democratic processes and change from the bottom-up

In this step we focus on two examples and methods on how to organise democratic processes that works closer to people and hopefully can inspire more meaningful action and wiser decisions.

Direct Democracy and Citizens’ Assembly on Climate

Direct democracy is when the decisions of government (such as laws and budgets), community, organisation or group are decided by residents, participants or members. This is unlike representative democracy, when the person elected makes decisions on behalf of the the electorate. Direct democracy is a form of distributed leadership, where everyone is engaged in decision-making.

Other forms of participatory democracy can take the form of citizens assemblies, where a demographically representative group of citizens discuss a particular issue to advise a parliament, or participatory budgets, where all city residents have a say in how money is spent. Organisations such as Digidem lab work on developing tools and digital platforms for these kinds of civic engagement. In this video the French citizens’ assembly on climate change is summarised and discussed.

Consensus Decision Making

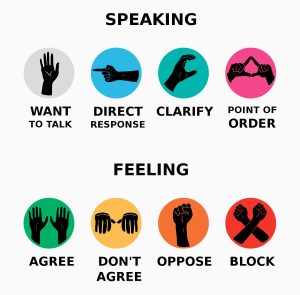

In consensus decision making, the goal is to come to an agreement which everyone in the group has consented to. This doesn’t necessarily mean that everyone is happy, but they have allowed the decision to be made and are comfortable with the group acting on it. This is in contrast to voting, where there will be some people who have voted against a decision and therefore have had to bend to the will of the majority. Consensus is popular in grassroots community and activist groups because it should allow everyone’s voice to be heard.

Hand signals used by the Occupy movement, by Ruben de Haas, CC BY-SA 3.0.

In consensus decision making it is important to have a skilled facilitator. This role is a form of temporary leadership, which is generally adopted by a volunteer for one meeting and then rotates to someone else the next time. The facilitator manages who should speak based on when they raise their hand, whether they have a direct point or are changing the subject, and whether they have spoken before. They keep the conversation on topic and may initiate decisions or summarise other participants’ points into proposals. They may also keep track of time and initiate breaks or future meetings. This person is not a boss or a teacher: a key skill of a good facilitator is the ability to listen to others and stay relatively neutral. They may stay quiet as much as possible, and pass on the role to someone else if they have a lot to share on a particular subject.

In Emergent Strategy (2017), Adrienne Marie Brown writes:

One of the primary principles of emergent strategy is trusting the people. The flip of Lao Tzu’s wisdom is: if you trust the people, they become trustworthy. Trust is a seed that grows with attention and space. The facilitator can be a gardener, or the sun, the water.

Often, facilitators seem to do the opposite of this. We sit with the organizers of a gathering and try to figure out ahead of time every single necessary conversation we want to see happen, and then create an agenda that imposes our priorities, or the organizers’ priorities, on the people who we have invited to gather, ostensibly because we care about what they think, or about what they are doing.

Then, a few hours or days into the gathering, we are harried and desperate because the people have realized what we are up to, or simply aren’t feeling heard, and/or we have missed something crucial that is at the center of the gathering. There emerges a sense of facilitators and participants working against each other, instead of everyone working in collaboration to meet the goals.

© CEMUS and Uppsala University