Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5

2.1

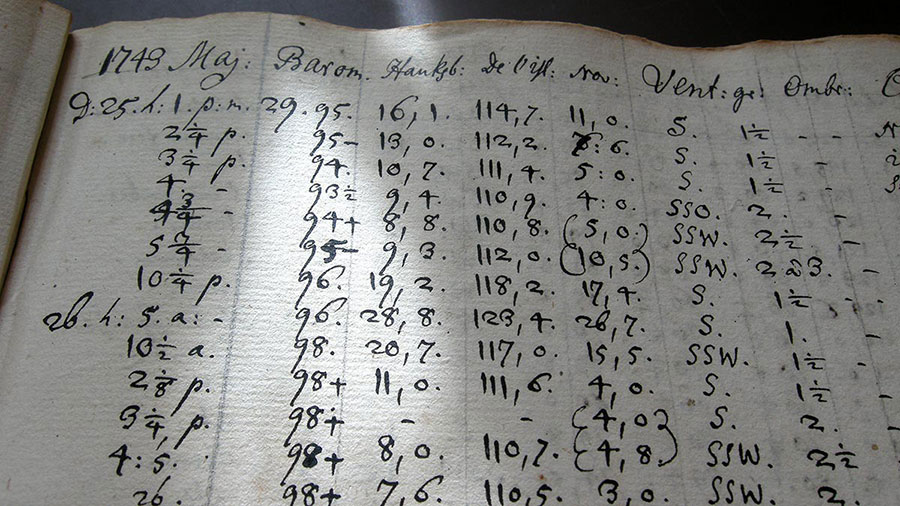

The meteorological journal the day the Celsius thermometer is being introduced, June 2 1743 [1] © Uppsala University.

Introduction: bending the curves to a sustainable future

Welcome to week 2 of the Climate Change Leadership course! Among other things, we will learn about:

- Climate targets, carbon budgets and emission reduction pathways to meet the 2°C target.

- Climate justice and how climate change highlights inequalities between countries.

- The difference between mitigation, adaptation and transformation as approaches to combat climate change.

Finally, we will reflect on our own role as climate change leaders and explore the multiple arenas in which climate change leadership can occur. You will identify and discuss a challenge that you are facing in your own context. You will continue to work with this challenge throughout the course.

Before we jump into the videos, quizzes and discussions for this week, here is a brief outline of the key concepts that we will cover.

Climate justice

One of the points brought up in Doreen Stabinsky’s video on the outcomes of the Paris Agreement is that some countries have more power in spaces of international decision-making than others do. This not only poses challenges when agreeing on certain legally binding or non-binding terms, but is also an example of injustice. An example of “climate injustice” is a global contradiction: countries in the Global North carry most of the responsibility for climate change (due to historically and persistently high emissions of carbon dioxide), yet countries in the Global South suffer most from the impacts, but are the least responsible [2].

This situation and the power dynamics it entails is one of the main political challenges that we face when dealing with climate change.

Both the drivers of climate change and its impacts are unevenly distributed. The photograph above shows the Mongstad oil refinery in Norway, and agriculture in the Panchkhal Valley in Nepal. Photo © Jakob Grandin.

When tackling climate change challenges, leaders must negotiate these global power dynamics even when working at a local level. Since these unequal dynamics are fundamental to how global society is organised, it seems what is needed is transformation rather than merely adaptation or mitigation.

Deliberate transformations and climate-resilient pathways

In discourse around climate change, “adaptation” refers to the “process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects”[3], whereas “mitigation” refers to reductions of greenhouse gas emissions in order to decrease the magnitude of global warming. Recently, “transformation” has been used to refer to an additional climate change response, which recognises the fundamental and systemic nature of social change needed to meet the climate change challenge. The IPCC defines transformation as:

A change in the fundamental attributes of natural and human systems. … [T]ransformation could reflect strengthened, altered, or aligned paradigms, goals, or values towards promoting adaptation for sustainable development, including poverty reduction.[4]

According to the IPCC “[t]ransformations in economic, social, technological, and political decisions and actions” may enable climate-resilient pathways [5]. These pathways combine emission reductions, adaptation measures and activities that increase social well-being in order to achieve sustainable development. The decisions that are made the coming years will hence determine both the magnitude of climate change that future societies will face, as well as the ability of these of these societies to deal with this climate change.

You will hear more on transformation as an approach to climate change leadership from Karen O’Brien, who notes that:

Choice refers here not only to adaptation, but also to our ability to shape the social and environmental conditions of the future. [6]

References

- The temperature and climate measuring series in Uppsala starting 1722, this image from 1743, read more about the series here.

- World Resources Institute (2014) The History of Carbon Dioxide Emissions.

- IPCC (2014). Summary for policymakers. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 5.

- IPCC (2014). Summary for policymakers. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 5.

- IPCC (2014). Summary for policymakers. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 29.

- O’Brien, K. (2012). Global environmental change II: From adaptation to deliberate transformation. Progress in Human Geography, 36(5), p. 668.

© CEMUS and Uppsala University